THIS POST is part of a series describing the rule changes I’ve made for my current fantasy role-playing campaign. “Kilgore’s Dungeons & Dragons,” or “KD&D,” is a full-fledged variant of the 1st Edition Advanced Dungeons & Dragons game initially released in 1977. Feel free to use some or all of these rule changes for your own D&D gaming, no matter what edition you play.

As I described in the inaugural post to this series, I’m running a 1e AD&D campaign for my friends. While I’ve always enjoyed AD&D, the game system itself can be clunky and difficult, and some parts are, frankly, lame.

To make what I consider to be improvements to the core rules, I’ve borrowed ideas from issues of Dragon magazine and later D&D editions, and have come up with a few of my own. My operating motto for re-tooling the game is to make it, “Simpler & Better.”

Last time out, I discussed magic-users, but making improvements to them was just the beginning: I’m going through each of the character classes and making them easier to play, and a lot more enjoyable. So, let’s move on to the magic-user subclass, and a favorite of mine and my players: the illusionist.

In the previous blog post, I described illusionists as uber-specialists. What I meant by that was, while magic-users in my campaigns may specialize in a wide variety of spells, limited pretty much only by their creativity and preferences, they may not specialize in illusions.

The study of illusionary magic is difficult and intensive, requiring dedication, focus, an exceptional mind (minimum Intelligence of 15), and superb fine motor skills (minimum Dexterity of 16). Only those who commit themselves wholeheartedly to it can hope to become a master of illusions.

In my campaign, only humans and gnomes can be illusionists, and each receives a bonus to experience points. As I explain here, humans get a 10% bonus as part of my attempts to make human characters more appealing. Gnomes get a 5% bonus because illusionists are their “favored class” (more about that here).

So, let’s talk about what I did to make illusionists “simpler & better.”

Resources

Spells for 1e AD&D were found in the Players Handbook (PHB), Unearthed Arcana (UA), and various issues of Dragon Magazine. When 2nd Edition came around, the Tome of Magic (ToM) was released.

The stuff in Dragon and ToM was, for the most part, okay, but nothing so earthshatteringly awesome that players couldn’t live without it. Also, it was a pain in the ass to look up stuff spread out across multiple sources (all those Dragon issues!) In a nod toward simplicity, it was an easy decision for me to rule that we’d only be using the PHB and UA.

Though I use the term “cantrips” below, I am not referring to the 0-level spells presented in UA, as I find them of little use or interest. Player-characters in previous campaigns never bothered with them, so I see no point in using them in my current one.

Magic-Users vs. Illusionists

Being a sub-class of magic-user, illusionists share a number of characteristics: hit dice, weapon choice, inability to wear armor and cast spells, pathetic close combat ability, saving throws, etc.

There are, however, some key differences between them, beyond just the higher scores required to become an illusionist. First off, per the PHB, illusionists gain no experience point (xp) bonuses for high Intelligence. This isn’t too big a problem, as they usually require about 10% fewer xp to advance a level.

Secondly, as depicted in UA, magic-users have many more spells available to them than illusionists do: the ratio is 5:2 for 1st-level spells (40 m-u spells, 16 illusionist spells), and it doesn’t get much better for the higher level magics. Thirdly, illusionists may only use certain magic items, as listed on page 26 of the PHB.

I’m okay with all of these. As I did for magic-users in the previous blog post, let’s look at illusionists’ ability to know and cast spells.

Knowing Spells

Understanding Spells. Whenever a player picks out spells for their character, they need to see if the illusionist understands them, as per Intelligence Table II on page 10 of the 1e AD&D PHB. The player rolls percentile dice, needing to get equal to or lower than the value listed in the table; if successful, the character can know the spell. If the number rolled is higher, the character can’t wrap their head around the spell, but can try again the next time they advance in level.

Having a minimum Intelligence of 15, illusionists have at least a 65% chance of understanding a spell, and one with INT 18 has an 85% chance. If the illusionist chooses to do a concentration, their chances for understanding Illusion/Phantasm spells can increase by 15%—more about that later.

The same table dictates the minimum number of spells of each level that can be known by an illusionist, as well as the maximum that they can know. I’ve thrown out that minimum number, as well as the cumbersome requirement that when an illusionist is able to cast a new level of spells, the player has to go through the list of said spells and see which one their character understands. In my campaign, a player only checks when his or her character is attempting to learn a spell.

Finishing off the table, I kept the maximum number of spells known per level. An INT 15 illusionist would know, at most, 11 spells per level, while an INT 18 illusionist could potentially know every spell there is.

Base Spell (“Cantrip”). First-level illusionists start off knowing one 1st-level spell of the player’s choice (provided the character understands it, of course). This spell is designated as a “cantrip,” and the illusionist may cast it as many times a day as desired (more about that later).

Additional 1st-level spells that the character learns later are not considered cantrips, nor can the player swap out their “cantrip” spell for another one: once they pick it, that’s what they have from then on.

Bonus Spells. Added to the base spell known would be bonus spells for high Intelligence, in the same way that clerics receive bonus spells for high Wisdom (see Wisdom Table II on page 11 of the 1e AD&D PHB). Illusionists thus gain bonus spells as follows:

- INT 15: Two 1st level and one 2nd-level spell

- INT 16: One 2nd-level spell

- INT 17: One 3rd-level spell

- INT 18: One 4th-level spell

As with clerics, these bonuses are cumulative (an illusionist with INT 16 gets two bonus 1st-level spells and two bonus 2nd-level spells), but the bonuses only apply if and when the caster has attained enough experience to use spells of that level. It doesn’t matter if you have a 17 Intelligence: you still can’t toss a Spectral Force until you’re 5th level.

Acquiring Spells at Each Level. Page 26 of the PHB has the table, “Spells Usable By Class and Level—Illusionists,” which denotes how many spells these characters can cast. I also use those numbers for determining spells known, not counting the bonus spells for high Intelligence.

Thus, at the start of their adventuring career, a 1st level illusionist will know three spells: their cantrip, and two others for high Intelligence. When the illusionist advances to 2nd level, they pick up another 1st-level spell: now they know at least four.

When they get to 3rd level, they pick up a 2nd-level spell (plus at least one bonus spell for high Intelligence), and when they get to 4th, they pick up another 1st-level spell and another 2nd-level spell. And so on, following the table, up to the maximum number of spells they can learn for each spell level.

Acquiring Spells By Other Means. Illusionists with even a smidge of ambition will want to find more spells to add to their collection. PCs are free to trade with each other, and NPCs can be paid or done favors for to gain more. Spells can be copied off magical scrolls (destroying the scroll in the process) or from spellbooks of enemy illusionists (making them a great magical find).

Again, illusionists are limited by their Intelligence to the number of spells per level that they can know. And no, they can’t swap out a spell known for another one: once they’ve picked and learned a spell, they have it for the rest of their lives.

Casting Spells

Similar to how they know spells, illusionists are able to cast a number of spells as shown on the table, “Spells Usable By Class and Level” on page 26 of the PHB. The number for each level is modified by Intelligence, as described above. In addition, an illusionist always has available to them their cantrip spell.

Thus, a 1st-level illusionist is able to cast their single cantrip and two other spells, making them much more useful. Under the old rules, a fledgling illusionist would be able to fire off one—and only one—spell per day.

At 2nd level, an illusionist can cast three spells in addition to their cantrips. At 3rd level, they add at least two and possibly three 2nd-level spells to their arsenal, and so on. Game play has shown me that these significant upgrades in spellcasting ability are not unbalancing, as we’re still talking about people with 4-sided hit dice and garbage armor class.

Casters in my campaign don’t need to pick out their spells ahead of time. Instead, they are free to choose what spell they want to use (from among their collection of known spells) on the fly, as situations develop.

Recovering Spells

One thing I’ve never liked about AD&D was all the downtime in between when a caster ran out of spells, and when they could start using them again, with the party shutting everything down until the caster was ready to rock ‘n’ roll. This was especially irritating at lower levels, when a party had only made it through a few rooms in a dungeon, but then had to camp or leave because their Friendly Neighborhood Prestidigitator had used his single spell for the day.

To get the casters (and thus, their parties) back on the field ASAP, I ruled that they need only rest one hour for the highest spell level that they were trying to recover. So, if all an illusionist was trying to get back was 1st-level spells, it would only take an hour to “recharge,” as it were.

If he/she was trying to get back 3rd-level spells, they would need three hours—but once those three hours were up, they would have all their 1st- and 2nd-level spell slots restored, too. And so on.

Concentration

As I detailed in the previous post, magic-users in my campaign are allowed to specialize in certain types of spells: fire spells, cold spells, combat spells, detection spells, divination spells, etc. All sorts of spells, that is, except illusions, because I wanted to maintain the illusionist as its own character class. To me, illusionists are uber-specialists, dedicating themselves to very difficult sorcery.

Even so, why should magic-users have all the fun? At the start of their adventuring career, illusionists can choose to take a concentration in Illusion/Phantasm spells: really, it’s just specialization by another name. Doing so incurs a 20% penalty to experience points gained, which can be mitigated by bonuses that would normally be had by playing a human or gnome.

When rolling to see if their character can understand a spell, players of illusionists who take a concentration get +15% for Illusion/Phantasm spells, so one with an 18 INT will automatically (100%) be able to understand one.

When casting Illusion/Phantasm spells, an illusionist who has taken this concentration is treated as being two levels higher with regards to range, area of effect, etc. These characters get +1 on their saves against Illusion/Phantasm spells, and the targets of their Illusion/Phantasm spells make saving throws at -1.

Putting It All Together

So, what does a brand-new illusionist character look like in my campaign? Let’s consider Vladlena, a female gnome illusionist, ready to start her adventuring career. Vladlena has a Dexterity of 18 and an Intelligence of 16, so she more than meets the minimum requirements of the class. Her Intelligence score gives her two extra 1st-level spells, and two 2nd-level spells, when she reaches 3rd level and is able to use them.

Vladlena decides to concentrate in Illusions/Phantasm spells. Normally, she would gain a 5% bonus to experience points, because illusionist is the favored class of gnomes, but as she has decided to take a concentration, she incurs a 20% penalty on xp gained. In the end, the penalty will be reduced to 15%, and Vladlena’s player believes it’s worth it.

First up, Vladlena chooses her cantrip, which she’ll be able to cast as many times a day as she wishes. As she’s just starting out and doesn’t have any magical items to keep her safe, she attempts to learn Phantom Armor (from UA, pg. 67). With her INT 16, she has a 65% chance to learn this spell, and her player makes the roll to understand it.

As an illusionist, she will also know two more 1st-level spells, due to her high Intelligence. She wants to learn Color Spray and Phantasmal Force; she has a 65% chance to understand Color Spray, but because she’s taking a concentration in Illusions/ Phantasms, she gains a 15% bonus to learn Phantasmal Force. Her player rolls a 16 on percentile dice for Color Spray, and a 76 for Phantasmal Force, so she adds both of them to her spell book.

When it comes to casting spells, at the start of each day, a 1st-level illusionist can cast their cantrip, plus two more for Intelligence of at least 15, for three total. Vladlena can choose which of the two non-cantrip spells she knows—Color Spray or Phantasmal Force—as situations develop, supplementing them with her cantrip, Phantom Armor.

When she casts Phantasmal Force, she is counted as being 3rd level with regard to range, duration, area of effect, etc. because it is an Illusion/ Phantasm spell. So, her Phantasmal Force has a range of 9″ (6″, plus 3″ for being treated as 3rd level). Anyone attempting to disbelieve the Phantasmal Force would do so at -1 on their save. If Vladlena is confronted with an enemy’s Phantasmal Force (or any other Illusion/ Phantasm spell), she would have +1 on her save.

Phantom Armor and Color Spray use her actual level (1st) for determining spell effects. Equipped with her spells, Vladlena’s ready to jump into the campaign.

Changes to Spells

I also made some changes to the illusionist spells in the PHB and UA. The first is that I got rid of Read Illusionist Magic, because while: 1) it was mandatory that each illusionist knew it, it turned out that 2) it was hardly ever used in my campaign.

Instead, I ruled that illusionists, as part of their training, can read any magical writings they come across. In its place, I substituted a much more useful 1st-level spell: Charm Person.

Because new spellcasters need all the help they can get, I also rule that when they throw a Chromatic Orb (see page 66 of Unearthed Arcana), they get their Dexterity Attacking Adjustment (+1 for DEX 16, +2 for DEX 17, +3 for DEX 18) “to hit,” on top of the bonuses for various ranges. Vladlena, with her 18 DEX, would be +6 “to hit” any opponents within 10 feet indoors, or 10 yards outdoors.

The biggest change that I made is that I’ve ruled that illusions do not cause damage, and don’t directly harm or kill those creatures subject to them.

This neatly slices through the Gordian Knot that has given DMs and players fits about illusion spells ever since the PHB came out. The trouble all started with the description for the spell Phantasmal Force:

When this spell is cast, the [caster] creates a visual illusion which will affect all believing creatures which view the Phantasmal Force, even to the extent of suffering damage from phantasmal missiles or falling into an illusionary pit full of sharp spikes.

players handbook, pg. 75

Note that it is not specified how much damage is done, or what counts as a “believing creature.” And that’s just the beginning of all the issues with illusions being able to harm others.

I’m a huge E. Gary Gygax fan, but this is simply a terrible, ill-defined spell, open to all kinds of ambiguity and shenanigans, with the potential to seriously unbalance play. Dragon Magazine published several articles addressing this issue, and later editions of D&D also tackled it.

For a while in my campaign, I ruled that targets of illusions that caused damage would automatically get a saving throw vs. spell to determine if they fell for it. If they failed their save, they would take one d6 for every level of the illusionist, the damage assumed to be psychosomatic. If they made their save, they took no damage.

But given how low-level monsters have terrible saves vs. spell (orcs need a 17, for example), the party’s illusionist was mowing down huge swathes of them at a time, even though she was only 2nd or 3rd level herself.

Worse, the illusionist player (and the rest of the party) quickly got bored with her chucking illusionary mass-murder spells. “Ho hum, there are 100 kobolds in that room.” (Cast Phantasmal Force of a Fireball). “Okay, now there are only 7.”

Something had to give.

Hence, my rule that illusions do not directly cause damage, because, after all, they aren’t real. Sure, an orc might crap its pants thinking that the illusionist is spraying 100 arrows its way, but once those “arrows” hit the orc and nothing actually happens, the monster is going to realize that it was just a trick.

I say, “directly cause damage,” because it would be totally legit for an illusionist to use their spells to fool opponents and put them in harm’s way. For example, an illusionist could stand on one side of a chasm and cast the illusion of a bridge (where there is none), then goad a pack of orcs into trying to run across it. A black pudding could be made to appear like a puddle of water. Poisonous mushrooms could look like delicious apples. And so on.

The exception to this ruling about illusions not causing damaging are a few spells that specifically state that they inflict physical harm on the target(s). Those spells are:

- Phantasmal Killer (PHB, pg. 98)

- Shadow Monsters (PHB, pg. 98)

- Demi-Shadow Monsters (PHB, pg. 98)

- Shadow Magic (PHB, pg. 99)

- Demi-Shadow Magic (PHB, pg. 99)

- Shades (PHB, pg. 99)

- Weird (UA, pg. 71)

While some might say that removing the ability for illusions to directly cause damage nerfs illusionists, I believe it further differentiates them from magic-users. Furthermore, it encourages cleverness and creativity: the illusionist definitely becomes the character class for thinking players. Illusionists are meant to beguile, to mislead, to trick. And who doesn’t love a trickster?

Caveats About Illusions

In my campaign, there are two things need to be kept in mind regarding illusions.

The first is that illusions fool people (and monsters), but not Nature. No matter how real an illusionary bridge appears, it will not allow anyone, no matter how fervently they believe in it, to defy gravity and walk across it. Likewise, an illusionist cannot conjure up a fake cleric to heal themself or others.

The second is that unless stated otherwise in a spell description, the target of an illusion must actively disbelieve it to have any chance of avoiding its effects. If they disbelieve, they are required to make a saving throw vs. spells (with any bonuses/penalties for high or low Wisdom).

If they succeed, they see through the illusion, and perceive the situation as it actually is. If they fail, they continue to experience the illusion, though they might have the nagging suspicion that something isn’t right (“I could have sworn that there was a door right here”).

For example, an illusionist casts an image of a room being empty when it actually has an enormous stone statue inside it. Someone who has no idea of the contents of that room, or otherwise has no reason to doubt that the room is empty, will automatically see it as so.

If they wander about the room and bump into the unseen statue, or if they have been to that room before and know that a massive statue, very heavy and difficult to move, is supposed to be there, they might disbelieve, and thus be allowed a saving throw.

Furthermore, depending on the situation and the persons involved, some targets might automatically disbelieve certain illusions, and be granted significant bonuses (+4 or more) to saving throws vs. spells against them. Someone who’s lived in a modest-sized home for more than 20 years is not going to easily be fooled into thinking that their bathroom has vanished overnight.

This policy of “active disbelief” is directly opposite of how I used to adjudicate illusions before, where anyone who saw an illusion was automatically allowed a saving throw against it.

My reasoning back then was that a viewer might notice some discrepancy with the illusion (“Wait—that dog over there has two tails”), or a shimmering in the air at the borders of the illusion, or something else.

But again, that was when illusions were much deadlier, a lot easier to abuse, and a lot less interesting to play.

Material Components

Many spells require material components, bits and ends of odd things: to cast Wall of Fog for example, the illusionist needs “a pinch of dried split peas,” or the spell won’t work.

Dragon Magazine issue 81, from January 1984, had an extensive article on how characters could acquire material components, and how much they cost. My players and I never bothered with that, or with keeping track of many of each component their characters had (“Crumbs! I’m out of split peas!”), because that level of detail is tedious even to professional accountants.

In my current campaign, I assume that the spellcasters have enough of whatever material components they need for an extended period of adventuring, that they acquired them during down time, and that they paid for them out of their standard living expenses (I’ll discuss those in a future post).

Some spells have material components which aren’t common items that can be easily purchased or made. In keeping with my motto of “Simper & Better,” I’ve ruled that whenever an illusionist casts a spell that requires an esoteric/expensive item, they just pay for it right when they cast the spell, with the assumption that they bought the component ahead of time.

The only times I would ever get anal about material components would be: 1) if a caster couldn’t afford an item, or 2) if the caster suffered some calamity where they lost all their stuff.

Next Up

That’s all for illusionists. Next time out, I’ll continue talking about spellcasters, turning to clerics, and the surprising changes I made to them.

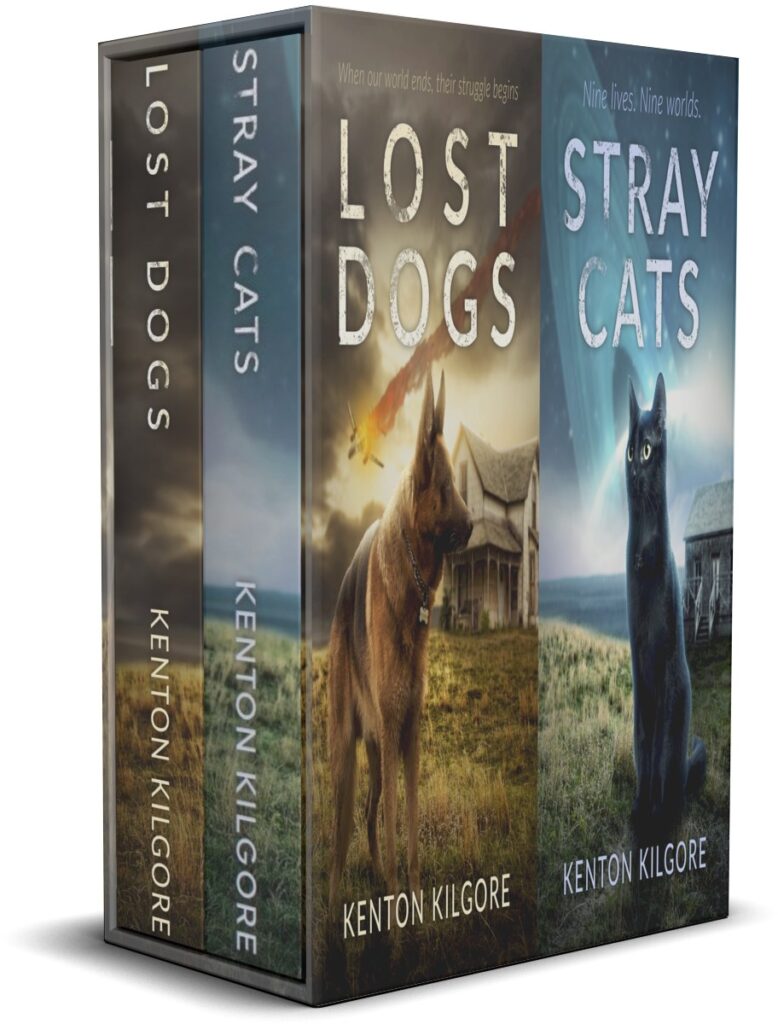

Kenton Kilgore writes books for kids, young adults, and adults who are still young. His most popular novels are Lost Dogs and Stray Cats, and now you can get them both for one low price in this Kindle box set, available only on Amazon for $4.99!

In Lost Dogs, when our world ends, their struggle begins! After inhuman forces strike without warning or mercy against mankind, Buddy, a German Shepherd, must band with other dogs to find food, water, and shelter in a world suddenly without their owners. But survival is not enough for Buddy, who holds out hope that he can find his human family again.

In Stray Cats, cats really do have nine lives–but they live them all at once, on different worlds. This follow-up to Lost Dogs features the adventures of Pimmi across the multiverse as she faces off against a cosmic menace threatening her and everyone she loves. But against such power, how can one small cat–even with nine lives–prevail?

Included in the boxed set are:

- An alternate ending for Lost Dogs;

- Lost Dogs original (2014) cover art;

- Excerpt from Kenton’s next fantasy novel, The Scorpion & The Wolf (coming 2025);

- Artwork from The Scorpion & The Wolf, by Alyssa Scalia

Dog lovers love Lost Dogs, and fans of felines adore Stray Cats. At last, you can have them both at one low price–get them now!