THIS POST is part of a series describing the rule changes I’ve made for my current fantasy role-playing campaign. “Kilgore’s Dungeons & Dragons,” or “KD&D,” is a full-fledged variant of the 1st Edition Advanced Dungeons & Dragons game initially released in 1977. Feel free to use some or all of these rule changes for your own D&D gaming, no matter what edition you play.

As I described in the inaugural post to this series, I’m running a 1e AD&D campaign for my friends. While I’ve always enjoyed AD&D, the game system itself can be clunky and difficult, and some parts are, frankly, lame.

To make what I consider to be improvements to the core rules, I’ve borrowed ideas from issues of Dragon magazine and later D&D editions, and have come up with a few of my own. My operating motto for re-tooling the game is to make it, “Simpler & Better.”

Last time out, I discussed the changes I made to spellcasting in general; for the next few articles, I’ll discuss the classes that cast spells, starting with magic-users. In my campaign, humans, high elves (but not wood elves), half-elves, and dwarves (yes, really!) can be magic-users.

As I explain here, human magic-users get a 10% bonus to experience points, as part of my efforts to make human characters more appealing. Half-elves and high elves receive a 5% bonus. The former do so to reflect their human heritage (and to make them more interesting to play). The latter receive the bonus because magic-user is their “favored class” (you can learn more about races and their favored classes here).

Humans, half-elves, and elves can combine their racial bonuses with the 10% bonus for Intelligence of 16 or more. Alas, dwarven magic-users don’t receive a racial bonus, but they’ll tell you that they’re just as good–if not better–at sorcery than any fumbling human or pointy-eared git!

Back when I started playing AD&D, in the Eighties, lots of gamers were not keen on magic-users, for a variety of reasons:

- Low hit points (d4)

- Limited choice of weapons

- Terrible in melee

- Not allowed to wear armor

- Slow to advance

Whether I was a player or a DM, I never had any issue with those restrictions: it’s true that low-level magic-users were about as tough as soggy toilet paper, but that’s the tradeoff for being able to cast spells and wield badass magical items.

No, my issues with the class were: 1) why they weren’t called “wizards,” “sorcerers,” or something—anything—cooler than the generic “magic-users.” And 2) how many spells they knew and could cast.

As for the former, though “magic-user” is a boring word, I’ve been using it so long that anything else sounds out of place. As for the latter, below are the rules for my campaign.

Resources for Spells

Spells for 1e AD&D were found in the Players Handbook (PHB), Unearthed Arcana (UA), and various issues of Dragon. When 2nd Edition came around, the Tome of Magic (ToM) was released.

The stuff in Dragon and ToM was, for the most part, okay, but nothing so good that players couldn’t live without it. Also, it was a pain in the ass to look up stuff spread out across multiple sources. In a nod toward simplicity, it was an easy decision for me to rule that we’d only be using the PHB and UA.

Though I use the term “cantrips” below, I am not referring to the 0-level spells presented in UA, as I find them of little use or interest. Player-characters in previous campaigns never bothered with them, so I see no point in using them in my current one.

Knowing Spells

Understanding Spells. Whenever a player picks out spells for their character, they need to see if the m-u understands them, as per Intelligence Table II on page 10 of the 1e AD&D PHB. When a magic-user wants to learn a spell, the player rolls percentile dice, needing to get equal to or lower than the value listed in the table.

A magic-user with an INT of 9 has only a 35% chance of understanding a spell, while one with INT 18 has an 85% chance. Spell specialization increases those chances by 15%—more about that later.

Given how many spells magic-users have available to them (there are 40 1st-level spells listed in UA) compared with other classes, I think it’s a fair tradeoff that they might not understand some of them.

The same table dictates the minimum number of spells of each level that can be known by a m-u, as well as the maximum that they can know. I’ve thrown out that minimum number, as well as the cumbersome requirement that when a m-u is able to cast a new level of spells, the player has to go through the list of said spells and see which one their character understands. In my campaign, a player only checks when his character is attempting to learn a spell.

If they fail to understand a spell, all is not lost. When the m-u advances in level, the player gets to roll again, if they want, to see if their character now understands spells that they didn’t earlier. I feel that this compensates for there no longer being a minimum number of spells known.

Finishing off the table, I kept the maximum number of spells known per level. An INT 9 wizard would only know, at most, 6 spells per level, while an INT 18 m-u could know up to 18 per spell level.

Base Spell (“Cantrip”). First-level magic-users start off knowing one 1st-level spell of the player’s choice (provided the character understands it, of course). This spell is designated as a “cantrip,” and the magic-user may cast it as many times a day as desired (more about that later).

Additional 1st-level spells that the character learns later are not considered cantrips, nor can the player swap out their “cantrip” spell for another one: once they pick it, that’s what they have from then on.

Bonus Spells. Added to the base spell known would be bonus spells for high Intelligence, in the same way that clerics receive bonus spells for high Wisdom (see Wisdom Table II on page 11 of the 1e AD&D PHB). Magic-users thus gain bonus spells as follows:

- INT 13: One 1st-level spell

- INT 14: One 1st-level spell

- INT 15: One 2nd-level spell

- INT 16: One 2nd-level spell

- INT 17: One 3rd-level spell

- INT 18: One 4th-level spell

As with clerics, these bonuses are cumulative (a m-u with INT 15 gets two bonus 1st-level spells and one bonus 2nd-level spell), but the bonuses only apply if and when the caster has attained enough experience to use spells of that level. It doesn’t matter if you have a 17 Intelligence: you still can’t toss a Fireball until you’re 5th level. And no, a m-u with mediocre Intelligence (12 or below) doesn’t have a chance of spell failure, unlike clerics.

Acquiring Spells At Each Level. Page 26 of the PHB has the table, “Spells Usable By Class and Level—Magic-Users,” which denotes how many spells a m-u can cast. I use these figures for determining the number of spells known, not counting bonus spells for high Intelligence.

Thus, at the start of their adventuring career, a 1st level m-u will know at least one spell (their cantrip) and up to three. When the m-u advances to 2nd level, they pick up another 1st-level spell: now they know at least two.

When they get to 3rd level, they pick up a 2nd-level spell (plus any bonus spells for high Intelligence), and when they get to 4th, they pick up another 1st-level spell and another 2nd-level spell. And so on, following the table, up to the maximum number of spells they can learn for each spell level.

Acquiring Spells By Other Means. Magic-users with even a smidge of ambition will want to find more spells to add to their collection. PCs are free to trade with each other, and NPCs can be paid or done favors for to gain more. Spells can be copied off magical scrolls (destroying the scroll in the process) or from spellbooks of enemy wizards (making them a great magical find).

Again, magic-users are limited by their Intelligence to the number of spells of each level that they can know. And no, they can’t swap out a spell known for another one: once they’ve picked and learned a spell, they have it for the rest of their lives.

Casting Spells

First Edition AD&D had two big rules about spellcasting, which I have substantially altered.

Memorizing Spells. One rule was that players needed to pick ahead of time which spells their characters were going to use during an adventuring session. If your m-u got knocked off a cliff, it didn’t help if they had Feather Fall in their spellbook but had chosen Magic Missile and Shield as their 1st-level spells for the day. Tough shit, pal: roll up a new character.

While you could argue that making players pick their spells beforehand would encourage them to choose a variety to cover likely situations, I found that the opposite happened. If a m-u in my campaign could memorize two 3rd-level spells, they were usually Fireball and Fireball. Or Fireball and Lightning Bolt. But it was never Infravision and Tongues.

Given the choice between damage-dealing spells that they knew would be useful in many or most circumstances, or non-combat spells that might be useful only in special situations, my players always took the former.

In my current campaign, magic-users can choose what spell they want to use (from among their collection of known spells) on the fly, as situations develop. The result is that players are more interested in acquiring and using a wider variety of spells, not just the ones that dish out damage.

Some DMs used to let casters trade out spell slots: for example, a m-u could give up two 1st-level spells for one 2nd-level, or vice versa. I’ve never gone for muddying the waters like that, I don’t see a reason to start now.

Forgetting Spells. The other big rule was that once a character cast a spell, it was wiped from their memory, and couldn’t be cast again that day (unless they had memorized it more than once). This was enacted under the assumption that if casters had no limit to the number of spells they could use, it would unbalance the game.

While tinkering with the rules, I experimented (with the players’ permission) with allowing casters to use their spells as many times as they wanted, while severely limiting their selection of spells. I found that at low levels, it made casters much more useful, and greatly helped the party’s survivability, but was not unbalancing.

As expected, though, once the casters gained levels and access to more—and more effective—spells, balance went quickly out the window. It got harder to challenge the party, with their supercharged spellcasters, without overwhelming them: no one wants a cakewalk or a TPK. So, I went back to the established “fire-and-forget” principle, which, while clumsy, works.

(By the way, the idea of a magic-user “forgetting” a spell just seems dumb to me. I prefer to think of it as the caster can harness a limited amount of magical energy at a time, with less-experienced wizards only able to toss a spell or two before running out of gas.)

Still, there was value in the experiment, as it led me to developing the rules for cantrips. In addition to making the m-u more useful and increasing their (and the party’s) survival, cantrips keep the game going (see “Recovering Spells,” below).

It’s true that by declaring certain spells as cantrips, a m-u can have unlimited Sleep spells, or Magic Missiles, or what have you. I view this as a feature, not a bug. I’ve found that at low levels, magic-users lean hard on these spells, but as they progress in power, they cast them less frequently, in favor of spells that use slots, but have more ooomph to them.

Recovering Spells

One thing I’ve never liked about AD&D was all the downtime in between when a caster ran out of spells, and when they could start using them again, with the party shutting everything down until the m-u was ready to rock ‘n’ roll again. This was especially irritating at lower levels, when a party had only made it through a few rooms in a dungeon, but then had to camp or leave because their Friendly Neighborhood Prestidigitator had used his single spell for the day.

To get the casters (and thus, their parties) back on the field ASAP, I ruled that they need only rest one hour for every level of the highest spell level that they were trying to recover. So, if all a magic-user was trying to get back was 1st-level spells, it would only take an hour to “recharge,” as it were.

If he/she was trying to get back 3rd-level spells, they would need three hours—but once those three hours were up, they would have all their 1st- and 2nd-level spell slots restored, too. And so on. So, yeah, it would take nine hours before an 18th-level magic-user could cast another Meteor Swarm: I’m good with that.

Specializing in Spells

For a number of reasons, I did not like 2e AD&D when it debuted in 1989, but in years since, I have nicked quite a few features of it for my campaign. One of those is allowing magic-users to specialize in the types of spells they cast. I tweaked the 2e rules in several places, and below is how spell specialization is done in my campaign.

To Specialize, Or Not To Specialize? Any magic-user, regardless of Intelligence or whether they are single, dual-, or multi-classed, can choose to specialize, but that must be done when the character is created (or, in the case of a dual-classed character, when they switch to being a m-u). Once the character starts adventuring, their choice is locked in. A magic-user may not change or pick up additional specializations: once they start down a particular path of study, they’re committed to it.

Choose Your Specialty. Second Edition AD&D based specialization around “schools of magic” based on the various spell types: enchantment/ charms, evocations, alterations, etc. Each school had an opposite school that the specialist could not learn or use.

I found this set-up to be artificial and lame. Would you rather your m-u be an “abjurer,” or a “combat mage?” An “evoker,” or a “pyromancer?” Yeah, that’s what I thought.

In my campaign, the player decides what general category of spells they want to specialize in, based on what direction they want their character to take. They can specialize in fire spells, water spells, combat spells, enchantments, words and languages, necromancy, mind-affecting spells, just about anything except illusions, which remain the purview of illusionists.*

*Second Edition removed the illusionist as a separate character class, but my players and I have always liked them, so they remain in my campaign. I rule that illusion magic is so difficult to learn that it requires those who would use it to devote themselves wholly to its study: think of illusionists as uber-specialists. More about them next time.

Cantrips of the appropriate type can be included among the specialized spells, so a pyromancer has the option of being able to cast Affect Normal Fires as many times a day as desired, with the benefits described below.

Costs And Benefits of Specializing. Magic-users who choose to specialize incur a 20% penalty to experience points gained. This can be mitigated by bonuses that would normally be gained for Intelligence scores of 16 or more (+10%) and/or by playing a human, half-elf, or high elf (as described above).

When rolling to see if their m-u can understand a spell, players of specialists get +15% for spells in the PC’s area of expertise, so a m-u with an 18 INT will automatically (100%) be able to understand a spell within their specialty area.

When casting specialty spells, the m-u is treated as being two levels higher with regards to range, area of effect, damage, etc. Thus, a 5th-level pyromancy drops 7d6, not 5d6, when they throw a Fireball. Specialists get +1 on their saves against magical attacks of the same type as their specialty. Those who are subject to their specialized spells make saving throws at -1.

Putting It All Together

So, what does a brand-new magic-user character look like in my campaign? Let’s consider Raina, a female high-elf magic-user, ready to start her adventuring career. Raina has an Intelligence of 17 and a Dexterity of 16, so she more than meets the minimum requirements of the class. Her Intelligence score gives her two extra 1st-level spells, two 2nd-level spells, and a 3rd level spell when she reaches the class levels to use them.

Normally, Raina would gain a 15% bonus to experience points: + 10% because of having an Intelligence of 16 or more; +5% because magic-user is the favored class of high elves. However, she has decided to specialize in fire spells, which calls for a -20% penalty. Adjusted accordingly, Raina will then have a -5% penalty to her advancement, but her player thinks it’s worth it.

First up, Raina chooses her cantrip, which she’ll be able to cast as many times a day as she wishes. She selects Burning Hands. Because she has a 17 Intelligence, she gets two bonus spells, so she chooses Cure Light Wounds (see “Changes to Spells,” below), and Shield.

With her INT 17, she has a base 75% chance to learn spells, but for Burning Hands, a fire spell, her chance is 90%. Her player rolls percentile dice for each spell, but doesn’t succeed for Shield. Instead, she chooses Spider Climb, and makes the roll with a 38. Upon attaining 2nd level, she can try again for Shield.

When it comes to casting spells, at the start of each day, a 1st-level magic-user can cast a base of one, plus two more for Intelligence of at least 15, for three total, not counting her cantrip. Raina can cast Burning Hands as many times a day as she likes, and can cast Cure Light Wounds and/or Spider Climb—deciding which as situations develop during the game—up to three times. She can cast Cure Light Wounds three times, or cast it twice and Spider Climb once, or any other combination, up to her limit of three times.

When she casts Burning Hands, she counts as being 3rd level with regard to range, duration, area of effect, etc. Anyone subject to her fire spells saves at -1; if she is attacked with fire spells, she saves at +1. Cure Light Wounds and Spider Climb use her actual level (1st) for determining spell effects. Equipped with her spells, Raina’s ready to take on the world.

Changes to Spells

I also made some changes to the spells in the PHB and UA. The first is that I got rid of Read Magic, because while: 1) it was mandatory that each m-u knew it (per the Dungeon Masters Guide), it turned out that 2) it was scarcely used in my campaign.

(And I can’t imagine any PC memorizing Read Magic at the start of their adventuring day just in case they run into some magical writing they need to decipher. Can you?)

Instead, I ruled that magic-users, as part of their training, can read any magical writings they come across. In its place, I substituted a much more useful 1st-level spell: Cure Light Wounds.

Yes, really, and yes, it can be a cantrip, but magic-users don’t get any of the other higher-level healing spells that clerics do. It might seem odd to you, but it makes sense to me that someone with 1-4 hit points should be able to use their magic to heal themselves. And if the m-u in the party can Cure Light Wounds, that takes some of the burden off the cleric.*

*As I’ll discuss in a future post, I’ve substantially altered clerics, so that they’re no longer generic Band-Aid boxes: indeed, some don’t even have healing spells.

Identify is a spell that just seems way too complicated for what it does. I’ve ruled that for each segment that the spell runs, the m-u will learn one fact about the magical item they’ve cast the spell on. So, for example, a 1st-level m-u would discover that a sword is +1 “to hit,” while a 2nd-level m-u would learn that it’s also +3 vs. lycanthropes and shape changers.

I’ve made small tweaks on other spells here and there, and probably will continue to do so when I see where one can be improved. I made a big change to illusion spells, but I’ll discuss that in my next blog post.

Material Components

Many spells require material components, bits and ends of odd things: to cast Fireball, for example, the m-u needs a tiny ball of bat guano and sulfur, or the spell won’t work.

Dragon Magazine issue 81, from January 1984, had an extensive article on how characters could acquire material components, and how much they cost. My players and I never bothered with that, or with keeping track of many of each component their characters had (“Crumbs! I’m out of bat guano balls!”), because that level of detail is tedious even to professional accountants.

In my current campaign, I assume that the spellcasters have enough of whatever material components they need for an extended period of adventuring, that they acquired them during down time, and that they paid for them out of their standard living expenses (I’ll discuss those in a future post).

Some spells have material components which aren’t common items that can be easily purchased or made. Identify, for example, calls for a pearl of at least 100 g.p. value. In keeping with my motto of “Simper & Better,” I’ve ruled that whenever a m-u casts a spell that requires an esoteric or expensive item, they just pay for it right when they cast the spell, with the assumption that they bought the component ahead of time.

Thus, when a m-u casts Identify, the player subtracts from their character sheet one of the 100 g.p. gems they have. If the character doesn’t have any 100 g.p. gems, they can just subtract 100 g.p. If they don’t have 100 g.p., perhaps another character can loan it to them. And so on.

The only times I would ever get anal about material components would be: 1) if a caster couldn’t afford an item. If the spell calls for a 10,000 g.p. gem but your character only has some copper coins in their pocket, they’re shit out of luck.

Or 2) if the caster suffered some calamity where they lost all their stuff. I’ve never done that bit where the DM starts off an adventure by telling the players, “Your character wakes up naked in a cell,” but if I did, the magic-users wouldn’t be tossing Fireballs to escape (at least, not right away).

Souping Up the Sorcerers

So, there you have it for magic-users in my campaign. I think the changes I’ve made make them more interesting and much more useful at lower levels. Next time out, I’ll discuss illusionists, the sub-class of magic-users, and the literal game-changing adjustments I made for them.

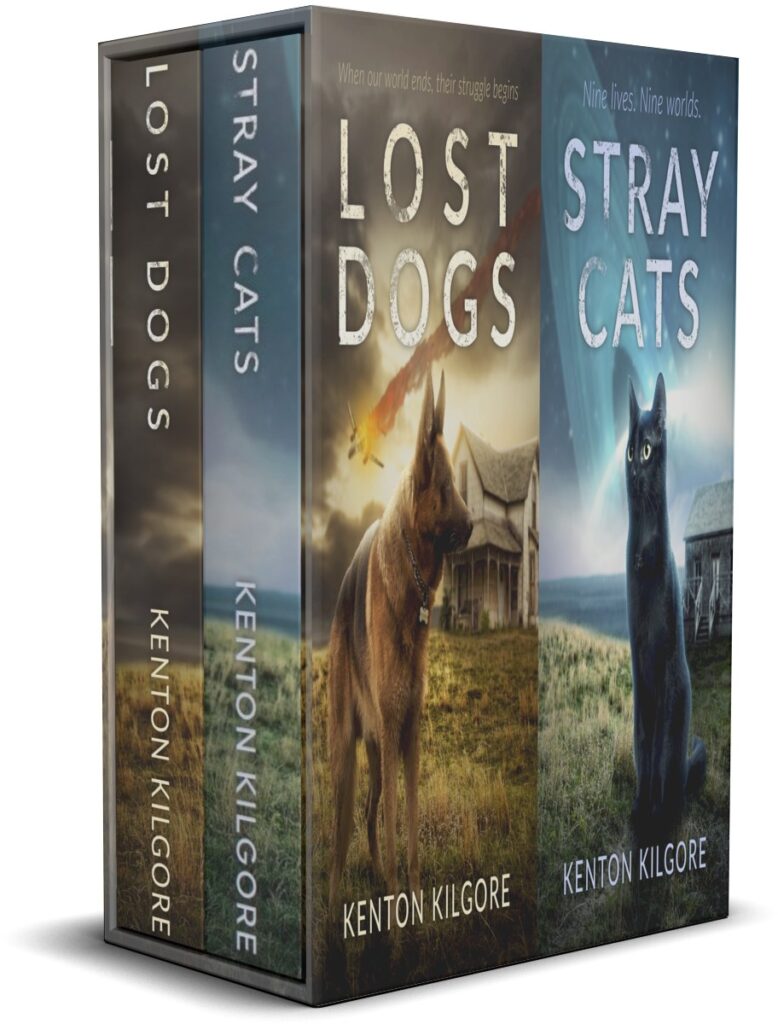

Kenton Kilgore writes books for kids, young adults, and adults who are still young. His most popular novels are Lost Dogs and Stray Cats, and now you can get them both for one low price in this Kindle box set, available only on Amazon for $4.99!

In Lost Dogs, when our world ends, their struggle begins! After inhuman forces strike without warning or mercy against mankind, Buddy, a German Shepherd, must band with other dogs to find food, water, and shelter in a world suddenly without their owners. But survival is not enough for Buddy, who holds out hope that he can find his human family again.

In Stray Cats, cats really do have nine lives–but they live them all at once, on different worlds. This follow-up to Lost Dogs features the adventures of Pimmi across the multiverse as she faces off against a cosmic menace threatening her and everyone she loves. But against such power, how can one small cat–even with nine lives–prevail?

Included in the boxed set are:

- An alternate ending for Lost Dogs;

- Lost Dogs original (2014) cover art;

- Excerpt from Kenton’s next fantasy novel, The Scorpion & The Wolf (coming 2024);

- Artwork from The Scorpion & The Wolf, by Alyssa Scalia

Dog lovers love Lost Dogs, and fans of felines adore Stray Cats. At last, you can have them both at one low price–get them now!